Table of Contents for

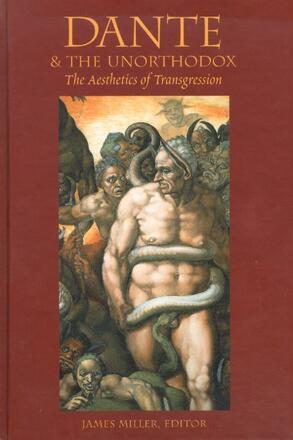

Dante & the Unorthodox: The Aesthetics of Transgression, edited by James Miller

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Retheologizing Dante | James Miller

PART I: Trapassar

Dante’s Limbo: At the Margins of Orthodoxy | Amilcare A. Iannucci

Saving Virgil | Ed King

Sacrificing Virgil | Mira Gerhard

PART II: Trasmutar

Dido Alighieri: Gender Inversion in the Francesca Episode | Carolynn Lund-Mead

Fuming Accidie: The Sin of Dante’s Gurglers | John Thorp

Heresy and Politics in Inferno | Guido Pugliese

Original Skin: Nudity and Obscenity in Dante’s Inferno | Mark Feltham and James Miller

Anti-Dante: Bataille in the Ninth Bolgia | James Miller

Part III: Trasumanar

Rainbow Bodies: The Erotics of Diversity in Dante’s Catholicism | James Miller

Dante/Fante: Embryology in Purgatory and Paradise | Jennifer Fraser

The Cyprian Redeemed: Venereal Influence in Paradiso | Bonnie MacLachlan

PART IV: Traslatar

“Dantescan Light”: Ezra and Eccentric Dante Scholars | Leon Surette

Ezra Pound in the Earthly Paradise | Matthew Reynolds

PART V: Tralucere

Dante and Cinema: Film across a Chasm | Bart Testa

“Moving Visual Thinking”: Dante, Brakhage, and the Works of Energeia | R. Bruce Elder

Driftworks, Pulseworks, Lightworks: The Letter to Dr. Henderson | R. Bruce Elder

PART VI: Trasmodar

Calling Dante: An Exhibition of Sculptures, Drawings, and Installations | Andrew Pawlowski and Zbigniew Pospieszynski

Curatorial Essay: Prophet of the Paragone | James Miller

Calling Dante: Notes on the Artists | James Miller

Calling Dante: A Portfolio of Words and Images | Andrew Pawlowski and Zbigniew Pospieszynski

Calling Dante: From Dante on the Steps of Immortality | Andrew Pawlowski

Notes on Contributors

Index

Notes on Contributors

R. Bruce Elder is an internationally acclaimed filmmaker, critic, and professor of film studies in the School of Image Arts at Ryerson University in Toronto. Retrospectives of his work have been mounted by the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), Cinémathèque Québécoise (Montreal), Senzatitolo (Trento, Italy) and Anthology Film Archives (New York). He is the author of Image and Identity: Reflections on Canadian Film and Culture (1989), A Body of Vision: The Image of the Body in Recent Film and Poetry (1997), and The Films of Stan Brakhage in the American Tradition of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson (1998).

Mark Feltham studied Dante and Bataille with James Miller in 1996–97 and completed his PhD in English at The University of Western Ontario in 2004. He specializes in James Joyce, with particular focus on editorial theory, electronic text theory, and the history of the book. He currently teaches English and writing at Western.

Jennifer Fraser completed her doctoral dissertation on Dante and Joyce at the University of Toronto in 1997. An instructor for the Literary Studies program at the University of Toronto in 2001–02, she has published articles in the James Joyce Quarterly and European Joyce Studies. Her book Rite of Passage in the Narratives of Dante and Joyce was published by the University Press of Florida in 2002.

Mira Gerhard graduated with a BA in classics from Brock University in 1994. She studied Dante’s Commedia with James Miller in 1996–97 at The University of Western Ontario, from which she graduated with an MA in classics in 1998. She continued her studies of Dante, Virgil, and the classical tradition at the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Toronto in 1998–99.

Amilcare A. Iannucci was director of the Canadian Academic Centre in Italy from 1981 to 1983 and chair of the Department of Italian Studies at the University of Toronto from 1984 to 1988. He is currently director of the University of Toronto Humanities Centre in University College. He is the author of Forma ed evento nella ‘Divina Commedia’ (1984) and of numerous articles on subjects ranging from Petrarch to Marshall McLuhan. Cofounder of the journal Quaderni d’italianistica, he is also the editor of Dante e la ‘bella scola’ della poesia: autorità e sfida poetica (1993), Dante: Contemporary Perspectives (1997), and Dante, Cinema, and Television (2004). An associate editor of The Dante Encyclopedia (2000), he has also produced an educational video series on The Divine Comedy.

Ed King earned his honorary TS (a transgressive T-Shirt bearing the glowering face of the Poet) after completing all three courses in James Miller’s 1995–96 Dante cycle. He went on to graduate from The University of Western Ontario with a BA in political science and comparative literature in 1998 and an MA in political science in 1999. His Master’s thesis was on economic rhetoric in Machiavelli’s The Prince. In 2004 he graduated with a PhD in political science from the University of California at Berkeley and joined the faculty in the Department of Political Science at Concordia University in Montreal. His main research interests include economic rhetoric and the effect of the imagination on political choices.

Carolynn Lund-Mead is a Toronto-based independent scholar whose publications include “Notes on Androgyny and the Commedia” in Lectura Dantis (1992) and “Dante and Androgyny” in Dante: Contemporary Perspectives (1997). Her doctoral dissertation on the relationship of fathers and sons in Virgil, Dante, and Milton reflects her strong interest in intertexuality, as does her present research for a project on Dante’s biblical allusions in collaboration with Amilcare A. Iannucci.

Bonnie MacLachlan is an associate professor in the Department of Classical Studies at The University of Western Ontario. She is co-editor of Harmonia Mundi: Music and Philosophy in Ancient Greece (1991) and author of The Age of Grace: Charis in Early Greek Poetry (1993). Her articles include “Sacred Prostitution and Aphrodite” (1992), “Personal Poetry” (1997), “The Ungendering of Aphrodite” (2002), and “The Mindful Muse” (2002). Her main research interests include ancient Greek and Roman religion, women in antiquity, ancient music, and the lyric poets Alcaeus, Sappho, Ibycus, Anacreon, and Corinna.

James Miller is Faculty of Arts Professor at the University of Western Ontario and founding director of the Pride Library (www.uwo.ca/pridelib). He is the author of Measures of Wisdom: The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity (1986) and the editor of Fluid Exchanges: Artists and Critics in the AIDS Crisis (1992). His cycle of Dante courses for the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures provides undergraduates with the rare opportunity to study the entire Dantean corpus over a period of two years. His next project is a study of gay readings/readers of the Commedia from Oscar Wilde to Derek Jarman.

Andrew Pawlowski (MD 1963; MD 1979) established himself in private practice as a dermatologist in Toronto and joined the University of Toronto Medical Faculty in 1983. After teaching himself how to sculpt, he served as the president of the Sculptors Society of Canada from 1992 to 1994. Besides numerous articles in medical journals, his publications include studies of the Polish-Canadian art scene and a cultural history of the Polish community in Toronto, The Saga of Roncesvalles (1993). Since his retirement from medical practice, he has written two novels set in the Middle Ages: Pochylony nad Łokietkiem (“Leaning over Lokietek,” published in 2004) concerning a Polish king in Dante’s time; and Zatrzymac cien Boga (“To Stop the Shadow of God,” forthcoming) on St. Bernard’s role in the Second Crusade. Photographs of his sculptures serve as illustrations for his books.

Zbigniew Pospieszynski studied painting and printmaking at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art, graduating with an MA in 1978. After immigrating to Canada in 1987, he has been active both as an artist and as a curator in the Toronto area. In April of 2004, he mounted a successful exhibition of his work under the auspices of the Roam Contemporary Gallery in New York City. He is currently director of the Peak Gallery in Toronto.

Guido Pugliese (PhD, 1974) teaches Italian literature and language at the University of Toronto at Mississauga. He has lectured on Dante, Boccaccio, Goldoni, Conti, Leopardi, Manzoni, and Verga, and has published articles on most of these authors. His scholarly interests extend to Italian theatre and questions of pedagogy. He has edited the previously unpublished correspondence of Pietro Ercole Gherardi to Muratori (1982) and a collection of papers entitled Perspectives on the Nineteenth Century Italian Novel (1989).

Matthew Reynolds is The Times Lecturer in English at Oxford University and a Fellow of St. Anne’s College. His book on Victorian poetry, The Realms of Verse, was published by Oxford University Press in 2001. He is co-editor, with David Forgacs, of Manzoni’s novel The Betrothed (Dent, 1997) and, with Eric Griffiths, of the anthology Dante in English (Penguin, 2005). His next book will be A Rhetoric of Translation.

Leon Surette (PhD, Toronto) is a professor emeritus in the Department of English at the University of Western Ontario where he has taught courses in modern British literature, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, James Joyce, William Golding, literature and philosophy, and literary theory. He is the author of A Light from Eleusis: A Study of Ezra Pound’s Cantos (1979), The Birth of Modernism: Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats and the Occult (1993), and Pound in Purgatory: From Economic Radicalism to Anti-Semitism (1999). He is co-editor of Literary Modernism and the Occult Tradition (1996) and I Cease Not to Yowl: Ezra Pound’s Letters to Olivia Agresti (1998).

Bart Testa teaches film studies and semiotics as senior lecturer in the Cinema Studies Program at Innis College, University of Toronto. He is the author of Spirit in the Landscape (1989), Richard Kerr: Overlapping Entries (1994), and Back and Forth: Early Cinema and the Avant-Garde (1992). His numerous articles on cinema include “An Axiomatic Cinema: The Films of Michael Snow” (1995), “The Double-Twist Allegory: Denys Arcand’s Jesus of Montreal” (1995), and “Seeing with Experimental Eyes: Stan Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes” (1999). He has served as books editor of the Canadian Journal of Film Studies and has long been a regular contributor to The Globe and Mail.

John Thorp THORP studied philosophy at Trent University in Canada and at Magdalen College, Oxford. He taught for the first half of his career at the University of Ottawa, and now teaches at The University of Western Ontario in London. He is the author of Free Will: A Defence against Neurophysiological Determinism (1980) and of numerous articles, including “Aristotle on Probabilistic Reasoning” (1994), “Aristotle’s Rehabilitation of Rhetoric” (1993), and “Aristotle’s Horror Vacui“(1990). His particular field of research is ancient thought, especially the thought of Aristotle. He is past president of the Canadian Philosophical Association.